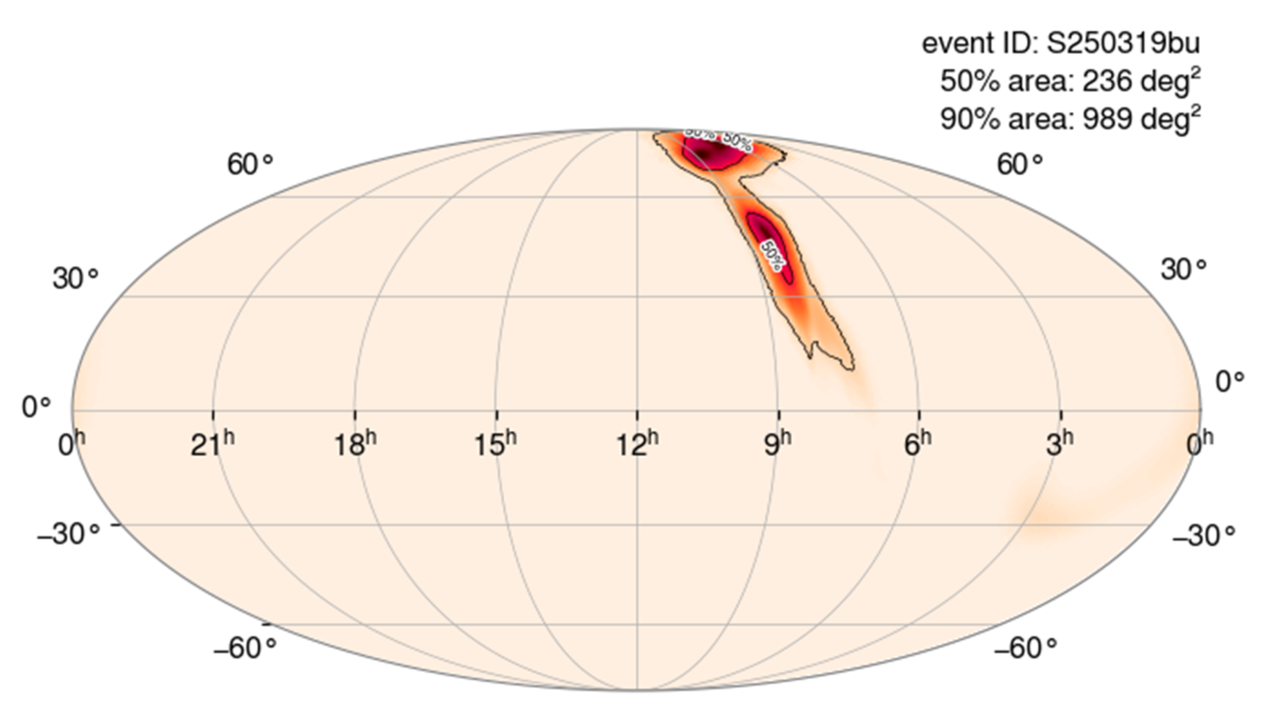

SkyMap indicating from where in the sky the LVK 200th gravitational wave candidate of O4 detection is thought to have originated.

LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA Announce the 200th Gravitational Wave Detection of O4!

News Release • March 20, 2025

By Kimberly Burtnyk (LIGO Laboratory) with contributions from the LVK communications team

On March 19, 2025, the international network of the LIGO, Virgo and KAGRA gravitational-wave observatories recorded the 200th gravitational wave candidate event of the current and ongoing observing run, O4. All of O4’s candidates are now being thoroughly investigated. They have also been immediately reported to astronomers worldwide via NASA's General Coordinates Network, and the Scalable Cyberinfrastructure to support Multi-Messenger Astrophysics. Interested scientific communities around the world are now looking forward to learning exciting new information about the astrophysics of black holes and neutron stars, the nature of gravity, and the evolution of our Universe.

Members of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration around the globe are celebrating this achievement.

Francesco Di Renzo, Postdoctoral Researcher, Institut de Physique des 2 Infinis de Lyon, Virgo collaboration: “Beyond its scientific impact for the whole astronomical community, this effort has been a powerful catalyst for [global] collaboration, fostering synergies among members who may be geographically distant or come from different research fields.”

Keita Kawabe, Senior Scientist, LIGO Hanford Observatory, Caltech, LIGO Scientific Collaboration: “[After 9.5 years of discoveries, the] detection of gravitational waves is not a special occasion anymore, it's a part of our daily lives. In O4 alone, over the course of 82 weeks so far, a total of 200 significant public alerts have been handled by a team comprising hundreds of individuals affiliated with Virgo, KAGRA and LIGO. [Moreover, a] vast majority of these alerts first became available for the public merely 10 seconds or so after [each] detection.”

Takahiro Sawada, Associate Professor, Institute for Cosmic Ray Research, University of Tokyo, KAGRA Collaboration: “Reaching the 200th candidate from O4 is a very emotional milestone. This achievement reflects the dedication of … and invaluable contributions of all collaborators across all fields within LVK. I extend my heartfelt gratitude to all collaboration members. Yet, this milestone is not an endpoint, but merely the beginning of new challenges. We are confident that many more groundbreaking discoveries await us, and we will continue this extraordinary journey alongside our esteemed colleagues.”

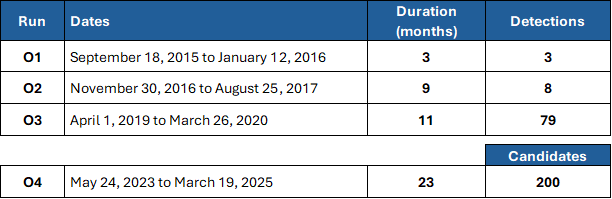

This latest event, believed to be a binary black hole merger, is a milestone discovery. In three previous observing runs (O1, O2, and O3) taking place over 23 months between September 18, 2015, and March 25, 2020, the international gravitational wave detector network recorded 90 gravitational wave detections. This latest run, O4, has now itself spanned 23 months, and candidate detections from O4 alone now number 200!

SkyMap indicating from where in the sky this latest candidate originated. Source: https://gracedb.ligo.org/superevents/S250319bu/view/

O1 to O3 included about 23 months-worth of observing time between 2015 and 2020. In that time, 90 GW detections were made. In the first 23 months of O4, 200 GW candidates have been logged. O4 is currently scheduled to end in November, 2025.

Event candidates are made public within minutes of their detection (there's even an app for that!) While some are later retracted after further analysis, information about all significant detection candidates is posted online. Catalogs of O1 to O3 discoveries are publicly availalble at the Gravitational Wave Open Science Center (GWOSC), and O4 candidate events are updated regularly in the Gravitational-Wave Candidate Event Database (GraceDB).

What are we finding?

Since the “advanced” era of gravitational wave detection began in 2015, the LVK network has now (as of March 19, 2025) recorded 290 GW events, which includes the 90 detections from O1 to O3, and the 200 candidates so far in O4. The vast majority of gravitational wave signals have come from colliding black holes. But the network has nabbed some more exciting and mysterious events:

- Two or three binary neutron star (BNS) mergers have been caught (there’s still some uncertainty in one event, hence “2 or 3”). Of those, the 2017 (O2) BNS merger is by far the most scientifically rich discovery to date, as it was observed both in gravitational waves and in electromagnetic (EM) light (gamma rays, visible, radio, etc.). Curiously, no subsequent BNS event is known to have been accompanied by an EM counterpart.

- Five or six candidates involving a neutron star colliding with a black hole. Uncertainty in the masses of one of these candidates accounts for the ‘or’ qualifier. In these cases, again, no EM counterparts have been confirmed, though one recent event may have been associated with neutrinos and a fast radio burst. Scientists are currently scrutinizing the data from that event to determine if the associations were real or just coincidences.

- And of special interest to the astronomical community, three or four events involving so-called “Mass Gap” objects, including an intriguing one detected in May 2024. The term “Mass Gap” refers to the fact that very few black holes or neutron stars with masses between 2 and 5 solar masses have ever been discovered, something that has perplexed astronomers for decades. The LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA network is starting to detect such objects, but since none of them have been observed in EM wavelengths, astronomers still don’t know exactly what they are: very massive neutron stars, or 'low-mass' black holes? Gravitational-wave detection efforts are beginning to fill in that gap.

Why so many?

The increase in candidate detections is due to continued efforts to improve gravitational wave detector technology and sensitivity. By the time gravitational waves (GW) arrive at Earth, they generate inconceivably small vibrations in our detectors (tiny fractions of the size of the nucleus of an atom.) To detect such impossibly small vibrations from space, GW detectors must eliminate as many Earth-based vibrations as possible. These include everything from earthquakes to local traffic around the detector sites, to the tiny vibration of molecules in the layers of coatings on optics within the instrument, to the unfathomably small quantum vacuum fluctuations that affect the detectors’ laser beams, which encode and deliver gravitational wave signals to our sensors. All these things are considered ‘noise’ to a GW detector, drowning out the already vanishingly small vibrations we want to feel. So, the more noise we eliminate, the more sensitive our detectors are to all gravitational waves. Continued efforts by LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA to find ways to prevent or filter out noise sources are contributing to the increased success and sensitivity of the global detector network.

Today’s gravitational wave detectors gauge their sensitivity by quantifying how far away they can detect colliding neutron stars, or BNS (binary neutron star) mergers. BNS mergers provide this baseline because they emit among the weakest gravitational waves that we expect to see with current detector technology. (If you want to know how good your hearing is, you don’t measure the loudest thing you can hear, you measure the faintest thing you can hear.)

Combining the measurements of noise in our instruments (which tells us the weakest GW signal that we could notice “above the noise”) with what is already known about the power and dissipation of gravitational waves from BNS mergers yields a maximum limit out to which the instrument can hope to see a “faint” BNS signal.

Keeping this in mind, in O1, at their best, the LIGO detectors’ BNS range hovered around 250 million light years. In O4, that range has more than doubled to about 550 million light years, not just increasing the distance to which we can detect binary neutron star mergers, but also, by default, improving our sensitivity to every other gravitational-wave-generating event in the Universe.

| Illustration showing how LIGO’s (in this case) BNS range has increased between O1 and O4. The map is centered on the Milky Way galaxy and spans about a billion light years. In O1, the BNS range encompassed the nearest 3 or 4 superclusters of galaxies. By O4, about a dozen superclusters were in range. Note that this map only shows the limits to detecting binary neutron star mergers. Since they are vastly more powerful, GW from black hole mergers occurring far beyond the confines of this map are detectable by today’s GW detector network. (Galaxy map: Richard Powell, atlasoftheuniverse.com/nearsc.html. Figure credit: Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab/Kim Burtnyk) | |