LIGO's Dual Detectors

Why Two Detectors?

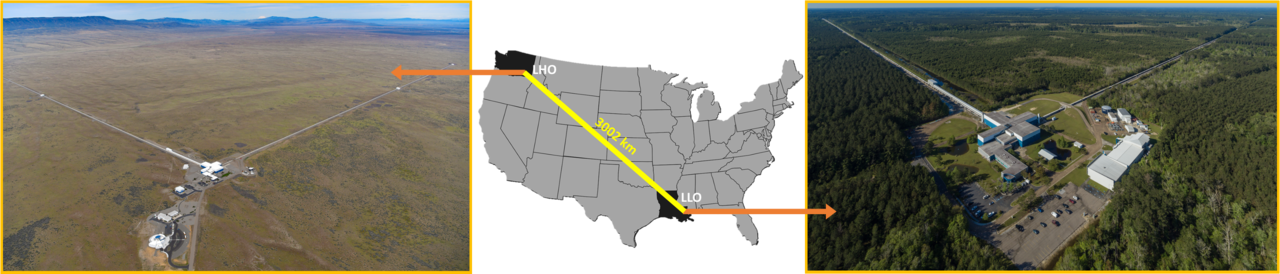

The U.S. National Science Foundation Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory is made up of two identical and widely separated interferometers situated in somewhat out-of-the-way places. The detector in Hanford, Washington is located in an arid, shrub-steppe region crisscrossed by hundreds of layers of ancient lava flows covered by rolling sand dunes created by Ice Age floods. The Livingston detector is situated in a completely opposite environment of a warm, humid, loblolly pine forest east of Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The instruments are 3002km apart and operate in unison as a single 'observatory', similar in manner to the multiple radio telescopes that make up sites like the Very Large Array (used in the movie, "Contact") in New Mexico, and the globally-dispersed radio telescopes comprising the "Very Long Baseline Array".

There are three crucial reasons for LIGO utilizing two interferometers, and for their wide separation: Local vibrations, gravitational wave travel time, and source localization.

First, NSF LIGO’s detectors are so sensitive that they can sense the tiniest vibrations on Earth. Earthquakes (anywhere in the world), traffic, agricultural activities, close-flying aircraft, lightning strikes, and even wind can cause disturbances that can mask or mimic a gravitational wave signal in each interferometer. If LIGO's instruments were located close to each other, they would sense the same vibrations (both the local Earth-based vibrations along with any actual gravitational waves) essentially at the same time, making it exceedingly diffcult to distinguish a gravitational wave signal from a non-gravitational wave signal in the data and to verify a GW detection. Two detectors separated by ~3000km experience unique local vibrations, and when data from the sites are compared, computers ignore vibrations that differ (the noise unique to each site), and hunt for only those vibrations that look the same. Comparing signals from the widely-separated interferometers is fundamental to LIGO's ability to claim a gravitational-wave detection.

Second, and equally as important, since gravitational waves travel at the speed of light, with detectors 3000km apart, the longest span of time that can elapse between a wave's arrival at LLO and LHO is about 10 milliseconds. Any similar signal that appears in both detectors more than 10ms apart is vetoed, since it could not possibly have been caused by a passing gravitational wave. Here again, two detectors are required for LIGO to operate as a single nation-wide observatory.

Another important reason for placing the detectors so far apart is to aid in localizing the source of the GW on the sky. While at least 3 detectors are needed to 'triangulate' a signal (like a cellphone's location can be triangulated by 3 or more cellphone towers), two can begin to narrow-down the region of sky containing the source of a GW signal. Each LIGO detector generates its own skymap. These are combined to create a single "LIGO" skymap that is then shared with collaborating electromagnetic (EM) astronomers who can scan those narrower regions of sky for any light possibly emitted by a GW event. But even two detectors can only do so much. The more GW detectors there are operating in unison around the world, the narrower the 'localized' patch of sky will be. This effect was fundamental to LIGO's and Virgo's historic detection of GW from colliding neutron stars in August, 2017. In that case, data from LIGO's two detectors, the Virgo GW detector in Italy, and two orbiting gamma ray observatories were combined to generate a skymap showing a tiny (by astronomer's standards!) region of the sky where the event had occurred. As soon as the Sun set (the patch of sky was still in daylight when the detection was made), astronomers who were able to see that part of they sky began imaging every galaxy contained in that small region. A team in Chile was the first to find and image the galaxy that hosted the source of the GW and EM signals. That event became the most studied astronomical event in human history (so far!)

Logistical Challenges

The requirement to build two detectors operating as a single observatory, their sheer size and extreme sensitivity to vibrations, and most importantly, the need to separate the detectors by thousands of kilometers presented significant challenges when deciding where to place the instruments. Potential sites were necessarily and deliberately selected in pairs. Finding one site large enough to build the instrument and its facilities in a reasonably remote location would be challenging enough; finding two such sites was an entirely different prospect. With population growth and urban sprawl, there are few places left in the U.S. where:

- two huge plots of land could be reserved for a massive, country-spanning science experiment requiring a lot of empty space around it,

- the local population density is reasonably low to minimize anthropogenic (human-generated) noise like traffic and farming activities, and

- the infrastructure (e.g., electricity, water) required to run the facility is within reasonable reach.

Overall, just as astronomical telescopes are built far from city lights that pollute the night sky with an obscuring fog ("light pollution"), gravitational-wave observatories need to be kept apart from vibrations caused by human activity. Such vibrations can drown out the telltale signals of gravitational waves in a sea of noise, just as light pollution drowns out the fragile light of distant stars. In the end, the desert of eastern Washington, and the forests of Louisiana were chosen as the locations of LIGO's two detectors.

Aerial photograph (taken in 2023) of LIGO Hanford Observatory showing the scale of the instrument and the locations of the "Corner Station" (where the laser is generated) and one arm's "End-Station", where the all-important test-mass mirror resides. Note that the arm is so long that the perspective distorts the distance between the Mid- and End-Station. (Credit: Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab)