LIGO Livingston's Gary Traylor unlocks one of the end test-masses (the mirrors at the ends of LIGO's arms) after it had been cleaned. The mirrors hang on 0.4mm thick silica glass fibers. Since cleaning the mirrors requires touching them, they need to be locked down to prevent them from moving while being cleaned, risking the integrity of the fragile, glass threads supporting them. (Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab)

LIGO's Commissioning Break Ends, O3 Resumes

News Release • November 4, 2019

By Kimberly Burtnyk

On November 1st at 15:00 UTC, the LIGO and Virgo gravitational wave detectors resumed their search for gravitational waves after taking a planned month-long break to perform some maintenance and upgrades. All three sites halted operations for the entire month of October (read LIGOs Commissioning Break Commences for information on some of the bigger projects that were planned at LIGO's Livingston and Hanford locations).

Staff, technicians, and engineers at both LIGO sites were extremely busy during the break. Combined, over 500 tasks were completed at Hanford and Livingston by October 31st! Two items mentioned in the pre-break story, namely LHO's wind fences and the leak search at Livingston, are still ongoing. Meanwhile at Virgo, engineers focused on increasing the laser input power from 19 W to 26 W, a task that required a complete re-tuning of the interferometer. Effort was also devoted to studying selected noise sources. Lessons learned from that study will improve Virgo's future operation. Virgo was also able to find the sources of some limiting noises and remove a few of them. To learn more about what Virgo accomplished in October, visit Virgo's story on their commissioning-break work.

The extent to which this work has improved the instruments’ sensitivities will be known in the weeks to come. The second half of LIGO's third observing run will conclude on April 30th, 2020.

Below are some photos taken of the work performed at all three facilities.

LIGO Livingston

LIGO Livingston completed over 300 tasks, small and large, during the break. Quite a feat! Among those, three of the biggest were inspecting and cleaning the mirrors at the ends of LIGO's arms ("test masses"), installing a metal shroud around a device that is used to help LIGO operators lock the interferometer, and installing light baffles of various shapes and sizes in several locations to eliminate scattered light. Livingston engineers were also tasked with finding and sealing a small leak in one of its vacuum tubes; that search continues. Below are a few pictures showing some of the bigger projects that were completed.

Test Mass Inspection and Cleaning

LIGO Livingston inspected and cleaned the mirrors (test masses) at the end of each arm. It is delicate, meticulous work, made all the more difficult by the fact that engineers need to wear ‘full bunny suits’ to work inside the chambers. The bunny suits make sure that any dust or skin cells or hair or other bits of stuff that humans are constantly shedding doesn’t contaminate the inside of the chamber or stick to the mirrors themselves (something that could have disastrous consequences if LIGO's powerful infrared laser were to vaporize such a mote of dust).

.jpg?1572634375)

Livingston engineer, Danny Sellers, paints the mirror with a substance called "first contact". This is used to help clean the mirror, which hangs at the bottom of a quadruple pendulum suspension system to isolate it from terrestrial vibrations. (Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab)

LIGO's optics expert, engineer, GariLynn Billingsley, inspects the surface of the mirror (test mass) at the end of LLO’s X-arm. The mirror hangs at the bottom of a quadruple pendulum suspension system to protect it from terrestrial vibrations. (Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab)

GariLynn Billingsley has marked a point absorber on the test mass at the end of the Y-arm. The ‘point absorber’ itself is the small dot in the middle of the screen. It is about 120 µm, or 1/10th of a millimeter, across. The ‘ribbon’ mark is a ~2mm circle drawn around the spot during a visual inspection. (Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab)

Inspecting the optic revealed one a problem spot called a point absorber in the coating on the mirror. GariLynn Billingsley, LIGO’s optics expert, explained why it is important to find them,

“[A point absorber] heats up in the presence of the laser beam. As you know, things get bigger when they heat up, so this causes a little mountain on our otherwise perfectly flat optic. When we get mountains on the optic, the interferometer beam resonates differently and causes excess loss [of photons] in the arms…thus making the detector less sensitive.”

Unfortunately, in this case, there is not a lot LLO can do to fix the situation, but knowing where they are is still important. It will also help LIGO and its coating vendors better-understand how to prevent the occurrence of such features in the future.

Shroud Installation and Light Baffles to Reduce Scattered Light

LIGO makes detections by examining the interference pattern generated by merging the laser beams coming from each arm. We use the laser beam like a ruler, telling us exactly how long the arms are at any given moment. This is why LIGO's laser must be incredibly stable (emitting one wavelength of light at all times) and that the waves of light comprising the beams in each arm remain properly oriented with respect to one another (their ‘phase’). If the light changed in any way, the resulting interference pattern could mask a gravitational wave.

Shroud Around TMS

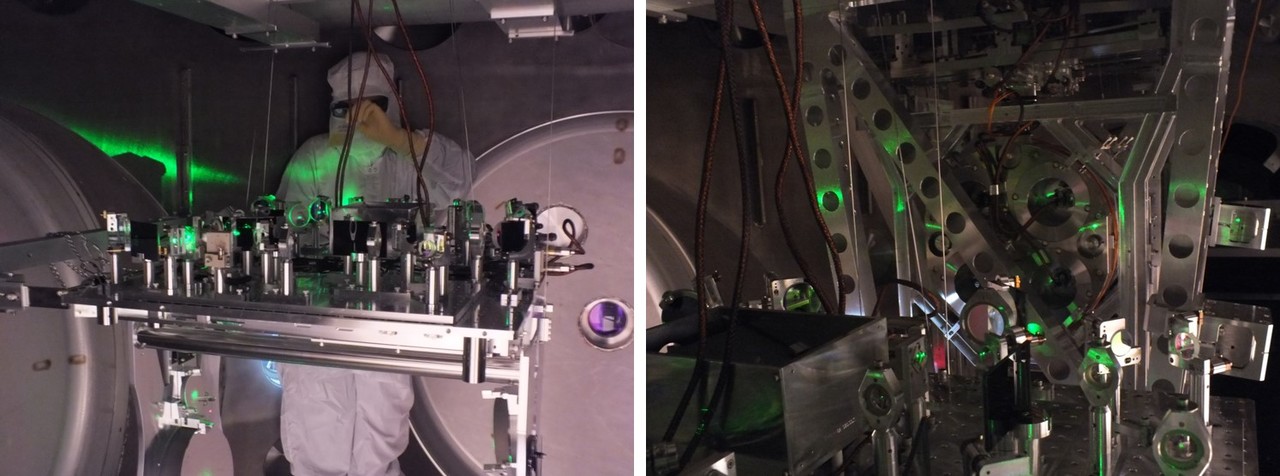

When LIGO Livingston discovered that there was some stray light bouncing around inside one of the vacuum chambers housing the Transmission Monitoring System, or TMS, they knew they had to do something about it. The TMS helps LIGO operators lock the interferometer so the instrument can sense gravitational-wave signals. A green laser is used during this locking process, but LIGO's invisible main near-infrared laser beam also travels through this device. Since the IR beam is invisible, the scattered green light indicates where the IR beam is also scattering inside the chamber. A problem arises when light (even infrared) bouncing off the walls of the chamber makes its way back into the main-beam path. This is because the chamber itself is not isolated from ground vibrations, so IR light reflecting off that 'vibrating' surface that makes its way back into the main-beam path will carry those vibrations along with them. These vibrations show up as noise in LIGO's output signal and can significantly decrease LIGO's ability to detect gravitational-wave vibrations. To remedy this problem, LIGO Livingston installed a shroud around one of their TMS devices to keep the light from scattering off the walls of the chamber.

Lots of scattered green light can be seeing coming off the TMS table. Here, LIGO Engineer, Anamaria Effler searches for the source of the scattered light. These scattered green photons indicate where LIGO's infrared laser beam (which also travels through the TMS) scatters inside the chamber. Since the walls of the chamber are not isolated from ground vibrations, any light reflecting off the walls that reenters the interferometer will include those vibrations. These vibrations can be seen in LIGO's output signal as 'noise', which hampers LIGO's sensitivity. (Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab)

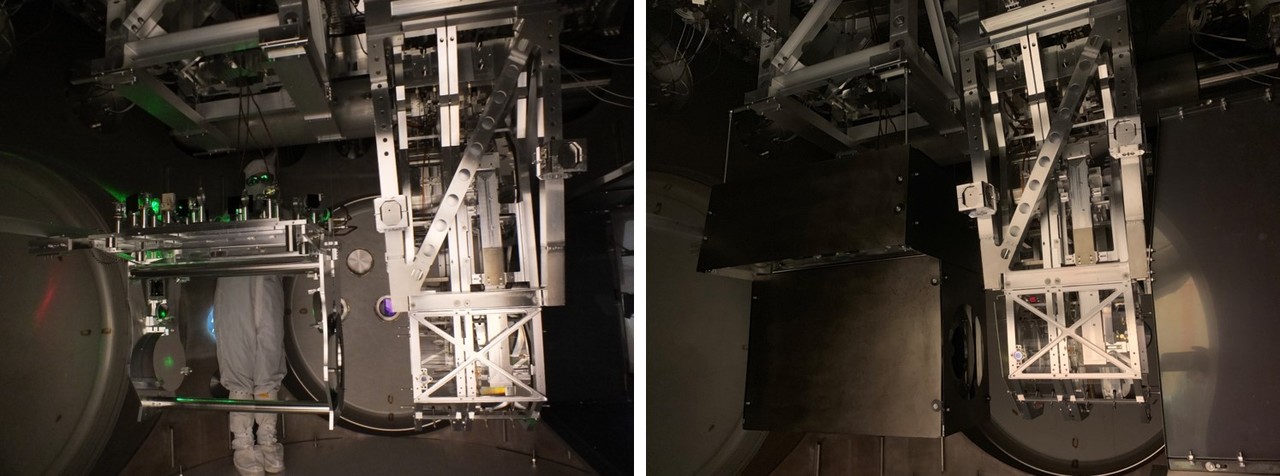

TMS structure before shroud installation (left) and after (right). Dr. Anamaria Effler provides a sense of scale. The large metallic structure on the right of both photos is one of LIGO's quadruple suspension systems. Here, just the lower three-quarters of the entire suspension is visible. "Quads" reside at the very ends of LIGO's arms. They each hold the mirror that reflects the laser beam back down each arm. The 40 kg mirrors or "test masses" hang at the bottom of a 4-chain pendulum (why they're called "quads"), suspended by 0.4 mm thick silica fibers actually fused to their surfaces. Hanging the mirrors in this way isolates them from ground vibrations, making them 'feel' like they are floating in space. (Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab)

Light Baffles

LIGO Livingston also installed stray light baffles in several different places inside the instrument, all designed to eliminate scattered infrared laser light, which degrades LIGO's ability to detect gravitational waves. The photos below show a large baffle panel being installed on the photon-calibrator (P-Cal) periscope in one of the vacuum tubes. The frame of the periscope is made of shiny metal, and it tends to move when the ground underneath the vacuum tube moves. Any scattered light bouncing from the surfaces of the periscope could also make its way into the path of LIGO's main laser beam. Just like the light bouncing from the chamber walls near the TMS, scattered light from the P-Cal periscope could transmit those vibrations into the instrument, and reduce LIGO's sensitivity.

Alena Ananyeva, who has led the baffle production effort and who helped install these baffles, explains how these baffles solve the problem of scattered light:

"The P-Cal baffles are made from a super-polished stainless steel coated with diamond-like carbon, an absorptive black coating. One can call such a baffle a black mirror. Imagine some scattered light comes in contact with one of these black mirrors. The black coating absorbs a significant fraction of infrared scattered light. Additionally, the baffles are formed or/and tilted in order to guide any light that is not absorbed by the black coating away from the test mass. The super polished surface of the baffles is essential to control direction of the reflection.”

Left: Research Specialist, Alena Ananyeva holds a segment of baffle prior to installation on the photon-calibrator periscope. Right: Ananyeva and PhD student, Corey Austin install one of the baffle segments. The mirror components of the "periscope" are partially visible as the silver 'tabs' to left and right of Ananyeva and Austin in the right-hand photo. (Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab)

LIGO Hanford

LIGO Hanford completed over 200 individual tasks, small and large, during the October break. Among those, some of the biggest were replacing some aging vacuum equipment, amputating an entire segment of the vacuum system that was not in use, and replacing a window between two HAM chambers that was scattering the laser beam that passed through it. LHO also replaced a fiber-optic cable in its laser squeezer device, and began construction of two wind fences, one at the end of each arm--As of November 1st, the wind fence was still under construction. Below are a few pictures showing some the work that was done during the break.

New Turbomolecular Pump

Chandra Romel (LHO Lead Vacuum Engineer) and Gerardo Moreno pose next to a newly-installed turbomolecular pump station. During the October break, three pumps and their associated controls systems were replaced as part of a 20-year vacuum lifecycle maintenance program. (Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab)

Since LIGO's vacuum system is so critical, it is important that all the systems designed to keep LIGO's vacuum as pristine and secure as it is are maintained at high levels. At LHO, that meant replacing some aging turbomolecular pumps (see photo at right). At 20-years old, the pumps had reached the end of their expected lifetimes, so replacements were ordered to make sure that LIGO Hanford's vacuum system will be secure for another 20 years.

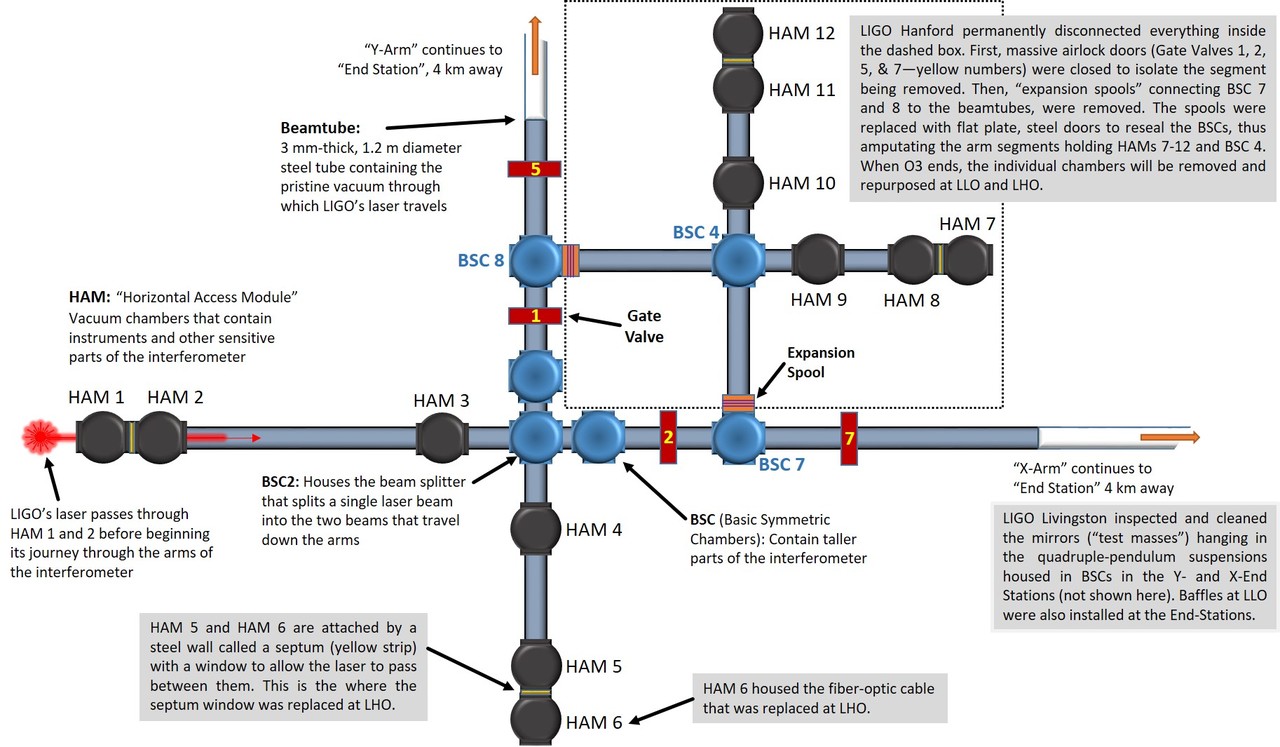

Decoupling "H2"

Also at LIGO Hanford, a large part of an unused portion of the vacuum system, called H2 (originally expected to house a second interferometer, which will instead be sent to India) was separated from the main vacuum system. Engineers removed two 'expansion spools' connecting the arms of H2 to BSC7 and BSC8 (see diagram) to the extra arm segments. BSC7 and 8 then had solid 'flat-plate' doors installed to seal those chambers. When O3 ends, the individual HAM chambers and the BSC chamber will be completely separated from the tube segments and repurposed at LLO and LHO.

The flat plate door is carefully lowered into the gap where the expansion spool was removed. (Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab)

Basic diagram (not to scale) of locations of HAM chambers and BSCs in the vertex (the area of LIGO's interferometer where its two arms meet). Text in shaded boxes references work done during the October 2019 commissioning break. Click to enlarge. (Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab/Kim Burtnyk)

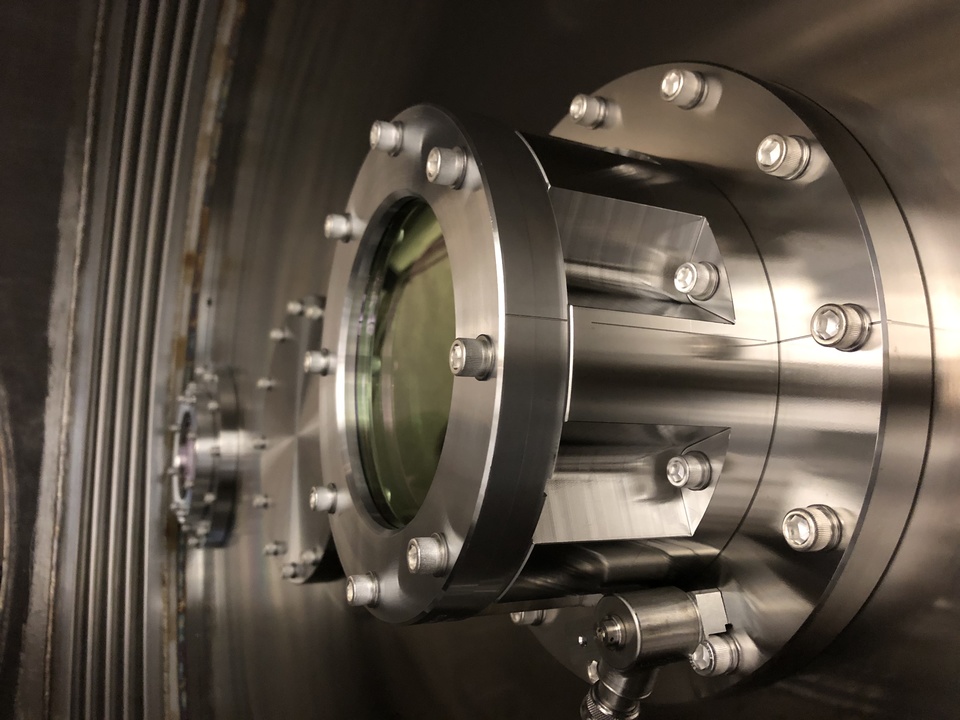

Septum Window Replacement

One additional task that LHO engineers weren’t sure they’d get to was replacing a ‘septum window’ between two HAM chambers (HAM 5 and HAM 6). LIGO’s laser beam passes through this window, and the (now) old one was scattering light, sending photons off in different directions. To eliminate this source of noise, LHO decided to replace the entire window assembly. The replacement went smoothly and the new window is scattering much less light than the old one. This should help to improve LHO’s overall sensitivity. Note in the images how shiny the metal interiors of the HAM chambers are. These shiny surfaces can be problematic if light reflects from them. So reducing scattering anywhere along the laser’s path is important to LIGO’s ability to detect gravitational waves.

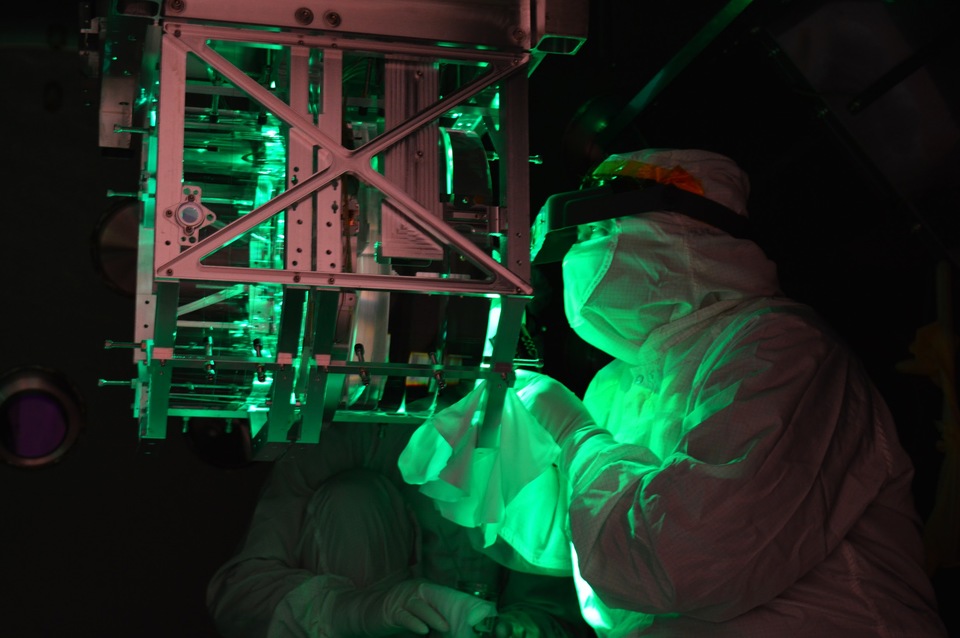

Engineers prepare to enter HAM 6 to install the new septum window between HAM 5 and 6. Both chambers are surrounded by portable clean rooms, and staff must wear 'full bunny suits' to enter. Here they are also wearing goggles to protect their eyes from any stray laser light. The open chamber on the left is HAM 6 and on the right his HAM 5. The structure visible inside HAM 6 supports the photodetector that ultimately detects gravitational waves. (Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab)

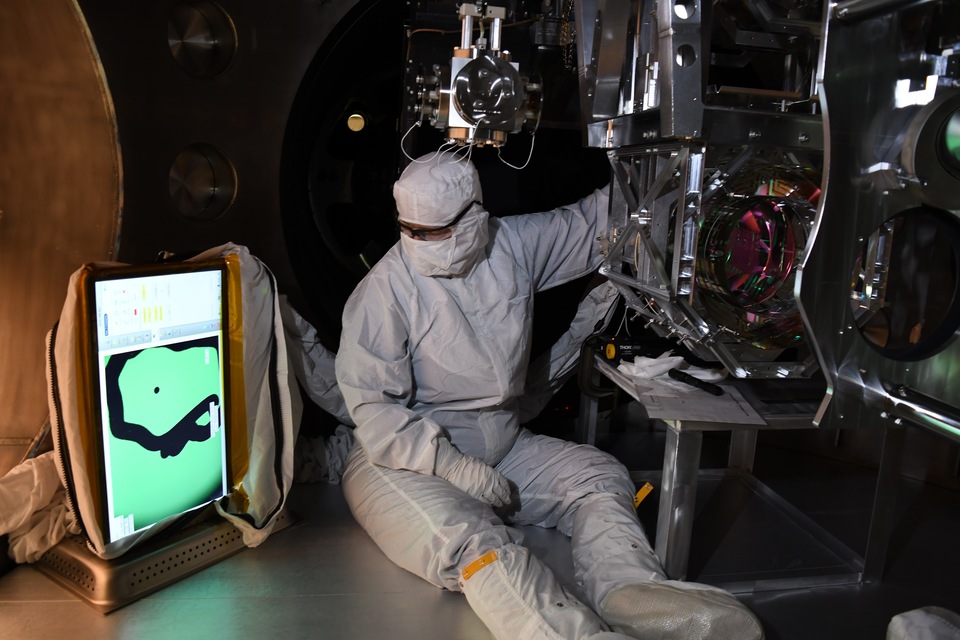

LHO engineers, Travis Sadecki and Gerardo Moreno, gingerly install the new septum window in the sealed door between HAM 5 and HAM 6. LIGO's laser passes from the arms of the interferometer, through this window, and into the photodetector. (Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab)

New septum window after installation. The old septum window was scattering light as the beam passed through it. The new septum window has resolved that problem. (Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab)